Anuj Puri, Chairman and Country Head, JLL India

Anuj Puri, Chairman and Country Head, JLL India

Mumbai, Delhi and Bangalore – all tier-I cities of India – rank at No. 4, 14 and 18 among most globalised emerging cities (see table below) in JLL’s new report Globalisation and Competition: The New World of Cities.

The report reveals interesting information about how ‘emerging world cities’ are integrating into the global economy; have become centres of demand-supply; the new world order of cities and how leading Indian cities stack up in all of these indices.

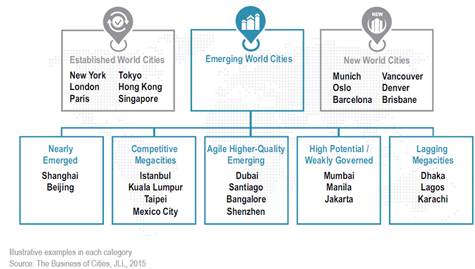

‘Emerging world cities’ are the business capitals of large domestic economies, and experience many of the scale, governance and implementation challenges of more established regions. Often supported actively by their national governments, they are in a process of economic adjustment and urban and metropolitan restructuring to optimise the benefits of global engagement.

Table: Most globalised emerging cities*

| City | GaWC Rank | Rank among Emerging Cities |

| Shanghai | 6 | 1 |

| Beijing | 8 | 2 |

| Dubai | 10 | 3 |

| Mumbai | 12 | 4 |

| Moscow | 14 | 5 |

| Delhi | 35 | 14 |

| Bangalore | 46 | 18 |

*With a GDP per capita below US$25,000.

(Source: GaWC, 2013; Brookings Global Metro Monitor, 2015)

In fact, the ongoing Globalisation and World Cities (GaWC) studies reveal big changes in the number and type of cities that are taking on international functions. Today, of the 100 most globalised cities according to GaWC data, 44 are middle-income and lower income cities with real GDP per capita of below US$25,000.

Nearly half of the cities that are driving the process of globalisation are located in the so-called ‘developing’ countries. They vary considerably in size, political context and development path. Their per capita income (by PPP) diverges significantly – cities such as Warsaw and Moscow are beginning to enter upper-middle or upper income status, while Indian and some Chinese cities are still closer to US$5,000 per annum. But the signs are that they all becoming rapidly integrated into the global economy, and their economic performance has become closely indexed to global demand.

‘Emerging world cities’ are centres of demand, supply

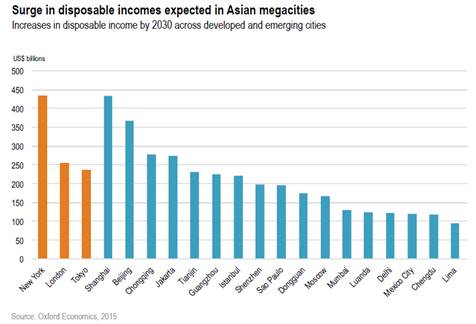

Between now and 2030, disposable incomes in Shanghai and Beijing are set to rise by over US$350 billion – more than in London and Tokyo – while consumer spending may increase by more than US$250 billion. Outside China, centres such as Jakarta, Istanbul and Mumbai are also seeing an urban consumer demand surge. This growth has big implications for the growth of the retail sector, and for the demand and supply of different kinds of space in these cities.

‘Established world cities’ used to host the overwhelming share of large global firms, but this picture is rapidly changing with 26% of firms having revenue above US$1 billion now being based in ‘emerging world cities’, and having the potential to reach 50% by 2025.

The new world order of cities

Mumbai has high potential and steps are being taken to strengthen governance

Manila, Mumbai and Jakarta are not only performing well at attracting real estate investment and outsourcing activities but also have more chronic infrastructure supply challenges compared to cities mentioned above. Transnational firms find these cities attractive as they expand their operations in South and South-east Asia, because of low costs and huge consumer market opportunities; however they face considerable urban infrastructure shortages.

For these types of cities to capitalise on their potential, their first priorities remain leadership, governance and coordination – all prerequisites to quality of life and economic ambitions. They need to reduce the complexity of preparing, assembling and executing projects, which prevents capital investment budgets from being fully deployed on a year-by-year basis.

They also rely on national policy to devise more effective plans for the national ‘system of cities’, and formal recognition from the national level of the unique burden of being a large globalising metropolitan area.

This was also the case in Mumbai until last year. However, there has been substantial improvement from then on. Steps have been taken to improve transparency, strengthen governance, and reduce red-tapism as also the complexity in execution of projects. For example, Mumbai civic corporation will cut building permissions from 150 to 70 and reduce the time taken to give building permissions within 90 days.

Maharashtra state government is also working on a plan to digitalise the permissions required by developers to bring transparency and is likely to finalise a part of the state housing policy by November-end.

Bangalore figures among agile higher-quality emerging cities

Agile higher quality emerging cities such as Bangalore, Warsaw, Santiago, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Colombo and Chengdu have attractive business environments, extensive development opportunities and comparatively well-educated populations that are allowing them to find niches in global supply chains.

Many have effectively leveraged property taxes, local user fees, and the monetisation of public land to invest in public services. These medium-sized emerging cities have some low-income housing and transport challenges, but fewer of the sprawling slum problems of other larger emerging centres. Typically, they are actively building international functions within the wider knowledge economy.

Dubai occupies a unique niche on the world stage. The emirate combines many characteristics of both established and emerging cities, thanks to its meteoric and unprecedented rise. Overall, however, the city’s attractive business environment and international profile, alongside its finance and knowledge-based strengths, mark it out as an agile higher quality emerging city.

Methodology:

The report authored by The Business of Cities and published by JLL, builds a new typology of cities based on the latest city performance indices. This research makes a breakthrough by adding three new concepts to the cities lexicon: ‘established’ world cities, ‘emerging’ world cities and ‘new’ world cities.

By employing data from over 200 city indices the report argues that it no longer makes sense to understand all cities as being in competition with every other city. Instead it shows how cities typically share similar classes of assets, challenges and trajectories with a small cluster of other similarly endowed cities. The paper concludes with examples of the imperatives cities in each different ‘type’ share if they are to manage their growth and development effectively in future. The full report can be read here.