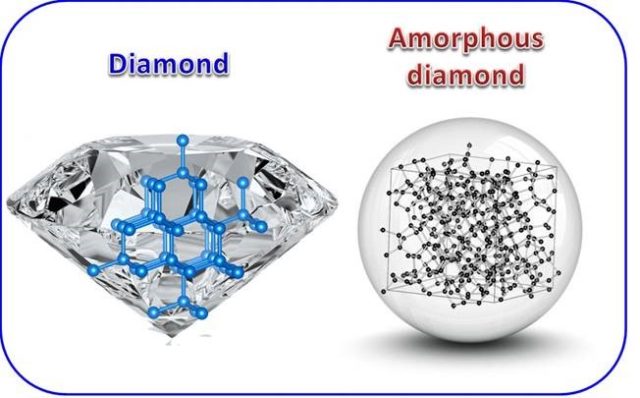

Washington, DC— A team of Carnegie high-pressure physicists have created a form of carbon that’s hard as diamond, but amorphous, meaning it lacks the large-scale structural repetition of a diamond’s crystalline structure. Their findings are reported in Nature Communications.

Carbon is an element of seemingly infinite possibilities, because the configuration of its electrons allows for numerous self-bonding combinations that give rise to a range of materials with varying properties.

For example, some forms of carbon, such as coal, are what’s called amorphous, meaning that they lack the long-range repetitive structure that makes up a crystal.

Other forms of carbon are crystalline, including both transparent, superhard diamonds, and soft, opaque graphite. They have different properties, in part, because the carbon atoms that comprise them are bonded in different configurations. Diamonds have a bonding structure that’s called sp3 and the carbon in graphite is held together with what’s called sp2 bonds.

Changes to the configuration of the carbon bonds that shape any of these substances can be induced by altering external conditions, such as temperature and pressure, similar to how water freezes into ice or boils into steam.

The Carnegie team—including lead author Zhidan “Denise” Zeng, as well as Liuxiang Yang, Qiaoshi Zeng, Yue Meng, Wenge Yang, and Ho-kwang “Dave” Mao—used extreme pressures to discover their new form of amorphous diamond.

Other similar elements to carbon—germanium and silicon—have forms that are comprised entirely of extremely strong sp3 bonds and yet amorphous. But until now, a similar phase of carbon had never been synthesized.

The team was able to create amorphous diamond by bringing a structurally disordered form of carbon called glassy carbon up to nearly 500,000 times normal atmospheric pressure (50 gigapascals) and about 2,780 degrees Fahrenheit (1,800 degrees kelvin). This is a temperature and pressure range than has not been explored in the efforts to create amorphous diamond.

The sample they created retained its structural change and incompressibility once it was returned to ambient temperature and pressure. What’s more, sophisticated spectroscopy tools demonstrated that their new material features sp3 carbon bonds, despite being amorphous and lacking the order of a crystal.

“Our amorphous diamond is dense, transparent, super-strong and potentially superhard with more incredible properties yet to be discovered,” Zeng explained.

The next steps for researching this amorphous diamond’s properties will be measuring its hardness, strength, optical properties, and thermal stability.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Thousand Youth Talents Program in China, the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science Basic Energy Sciences Materials Science and Engineering Division.

Portions of the work were performed at HPCAT, which is supported by the U.S. DOE with partial instrumentation funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation. Portions of the work were performed at the GeoSoilEnviroCARS sector of APS, ANL. Portions of the work were performed at the Center for Nanoscale Materials at ANL a DOE-BES facility, supported by University of Chicago Argonne, LLC.

The Carnegie Institution for Science (carnegiescience.edu) is a private, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with six research departments throughout the U.S. Since its founding in 1902, the Carnegie Institution has been a pioneering force in basic scientific research. Carnegie scientists are leaders in plant biology, developmental biology, astronomy, materials science, global ecology, and Earth and planetary science.