- The Global Competitiveness Report 2015-2016 finds countries need higher productivity to address sluggish global growth and persistent high unemployment

- Failure to boost competitiveness is compromising resilience to recession and other shocks, report finds

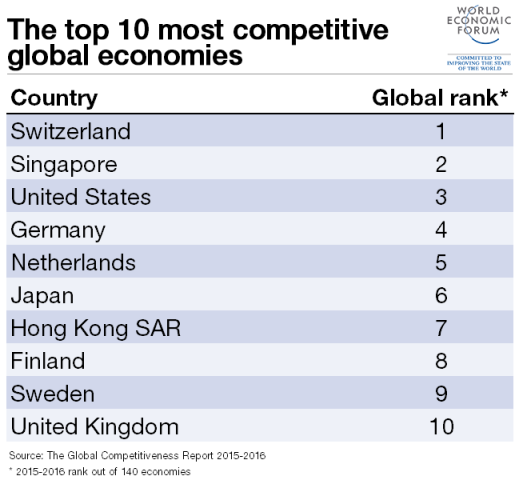

- Switzerland, Singapore and the US have been nurturing innovation and talent; this has kept them at the top of the Global Competitiveness Index, which profiles 140 economies

- Geneva, Switzerland, 30 September 2015 – A failure to embrace long-term structural reforms that boost productivity and free up entrepreneurial talent is harming the global economy’s ability to improve living standards, solve persistently high unemployment and generate adequate resilience for future economic downturns, according to The Global Competitiveness Report 2015-2016, which is released today.

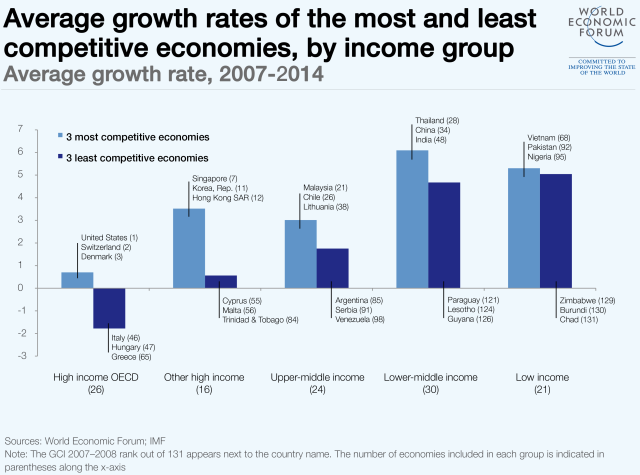

The report is an annual assessment of the factors driving productivity and prosperity in 140 countries. This year’s edition found a correlation between highly competitive countries and those that have either withstood the global economic crisis or made a swift recovery from it. The failure, particularly by emerging markets, to improve competitiveness since the recession suggests future shocks to the global economy could have deep and protracted consequences.

The report’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) also finds a close link between competitiveness and an economy’s ability to nurture, attract, leverage and support talent. The top-ranking countries all fare well in this regard. But in many countries, too few people have access to high-quality education and training, and labour markets are not flexible enough.

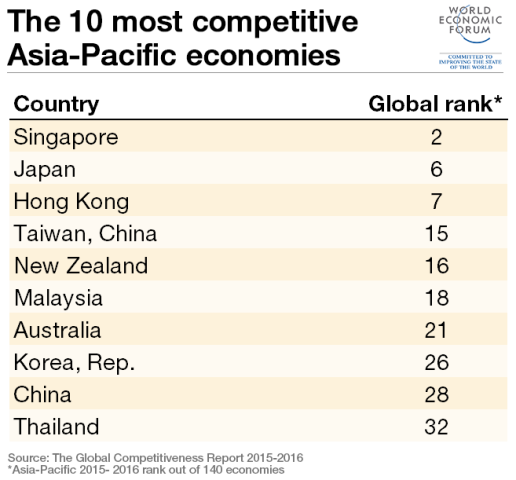

First place in the GCI rankings, for the seventh consecutive year, goes to Switzerland. Its strong performance in all 12 pillars of the index explains its remarkable resilience throughout the crisis and subsequent shocks. Singapore remains in 2nd place and the United States 3rd. Germany improves by one place to 4th and the Netherlands returns to the 5th place it held three years ago. Japan (6th) and Hong Kong SAR (7th) follow, both stable. Finland falls to 8th place – its lowest position ever – followed by Sweden (9th). The United Kingdom rounds up the top 10 of the most competitive economies in the world.

In Europe, Spain, Italy, Portugal and France have made significant strides in bolstering competitiveness. Thanks to reform packages aimed at improving the functioning of markets, Spain (33rd) and Italy (43rd) climb two and six places respectively. Similar improvements in the product and labour market in France (22nd) and Portugal (38th) are outweighed by a weakening performance in other areas. Greece stays in 81st place this year, based on data collected prior to the bailout in June. Access to finance remains a common threat to all economies and is the region’s greatest impediment to unlocking investment.

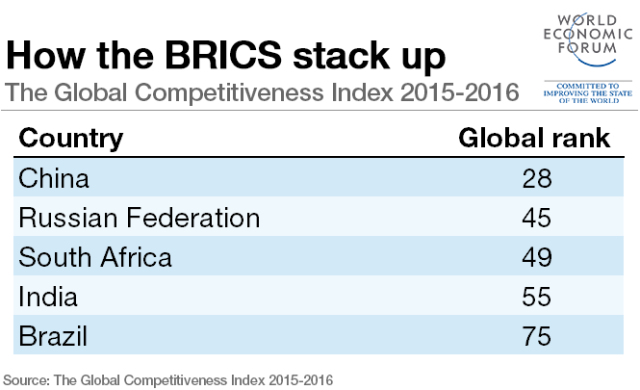

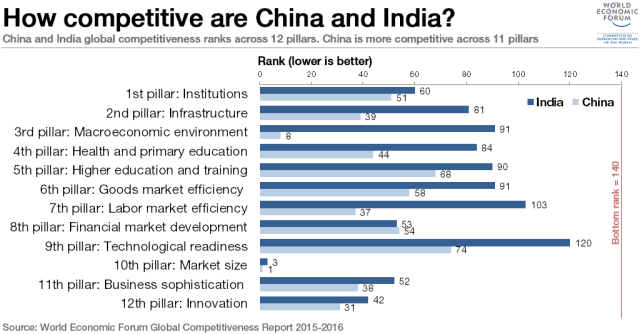

Among the larger emerging markets, the trend is for the most part one of decline or stagnation. However, there are bright spots: India ends five years of decline with a spectacular 16-place jump to 55th. South Africa re-enters the top 50, progressing seven places to 49th. Elsewhere, macroeconomic instability and loss of trust in public institutions drag down Turkey (51st), as well as Brazil (75th), which posts one of the largest falls. China, holding steady at 28, remains by far the most competitive of this group of economies. However, its lack of progress moving up the ranking shows the challenges it faces in transitioning its economy.

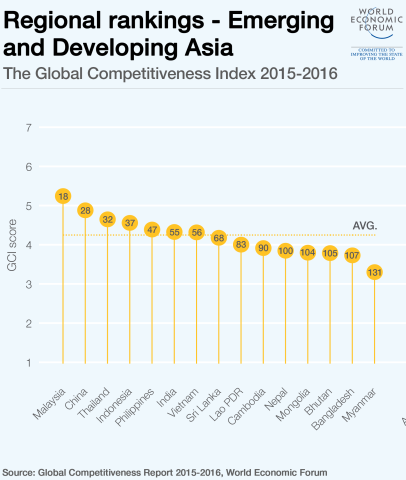

Among emerging and developing Asian economies, the competitiveness trends are mostly positive, despite the many challenges and profound intra-regional disparities. While China and most of the South-East Asian countries performing well, the South Asian countries and Mongolia (104th) continue to lag behind. The five largest members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) – Malaysia (18th, up two), Thailand (32nd, down one), Indonesia (37th, down three), the Philippines (47th, up five) and Vietnam (56th, up 12) – all rank in the top half of the overall GCI rankings.

The end of the commodity super cycle has strongly affected Latin America and the Caribbean, and is already having repercussions on growth in the region. Greater resilience against future economic shocks will require further reform and investment in infrastructure, skills and innovation. Chile (35th) continues to lead the regional rankings and is closely followed by Panama (50th) and Costa Rica (52nd). Two large economies in the region, Colombia and Mexico, improve to 61th and 57th, respectively.

It’s a mixed picture in the Middle East and North Africa. Qatar (14th) leads the region, ahead of the United Arab Emirates (17th), although it remains more at risk than its neighbour to continued low energy prices, as its economy is less diversified. These strong performances contrast starkly with countries in North Africa, where the highest placed country is Morocco (72nd), and the Levant, which is led by Jordan (64th). With geopolitical conflict and terrorism threatening to take an even bigger toll, countries in the region must focus on reforming the business environment and strengthening the private sector.

Sub-Saharan Africa continues to grow close to 5%, but competitiveness and productivity remain low. This is something countries in the region will have to work on, especially as they face volatile commodity prices, closer scrutiny from international investors and population growth. Mauritius remains the region’s most competitive economy (46th), closely followed by South Africa (49th) and Rwanda (58th). Côte d’Ivoire (91st) and Ethiopia (109th) excel as this year’s largest improvers in the region overall.

“The fourth industrial revolution is facilitating the rise of completely new industries and economic models and the rapid decline of others. To remain competitive in this new economic landscape will require greater emphasis than ever before on key drivers of productivity, such as talent and innovation,” said Klaus Schwab, Founder and Executive Chairman of the World Economic Forum.

“The new normal of slow productivity growth poses a grave threat to the global economy and seriously impacts the world’s ability to tackle key challenges such as unemployment and income inequality. The best way to address this is for leaders to prioritize reform and investment in areas such as innovation and labour markets; this will free up entrepreneurial talent and allow human capital to flourish,” said Xavier Sala-i-Martin, Professor of Economics at Columbia University.

The Global Competitiveness Report’s competitiveness ranking is based on the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI), which was introduced by the World Economic Forum in 2004. Defining competitiveness as the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country, GCI scores are calculated by drawing together country-level data covering 12 categories – the pillars of competitiveness – that collectively make up a comprehensive picture of a country’s competitiveness. The 12 pillars are: institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, health and primary education, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labour market efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness, market size, business sophistication, and innovation.