Post the 1991 liberalization policy, India began to welcome various multinational corporates that were seeking permission to commence operations locally. Being the financial and commercial capital of India, Mumbai was the first city to witness a significant influx of large multinational firms.

Post the 1991 liberalization policy, India began to welcome various multinational corporates that were seeking permission to commence operations locally. Being the financial and commercial capital of India, Mumbai was the first city to witness a significant influx of large multinational firms.

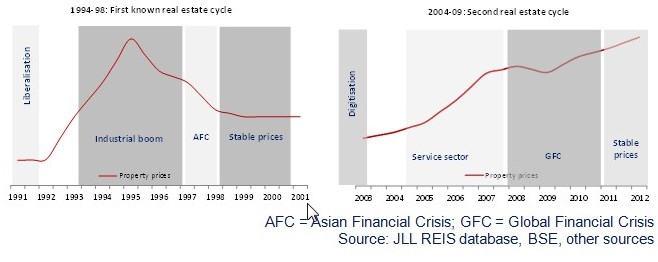

By 1994-95, real estate prices in the city increased to a point where companies started to look for cheaper alternative locations, paving the way for other cities to grow commercially. Demand for both commercial and residential real estate gathered steam.

A policy-driven bullish cycle culminated in an industrial boom, thereby also driving house prices to a peak in 1995. At this peak, some realities of the Indian economy (poor bank penetration, high interest rates, non-transparent real estate market, etc.) came to fore, bringing a correction in market prices. As the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) erupted in the late 1990s, residential prices witnessed a significant drop, returning to the levels witnessed in the early 1990s.

A policy-driven bullish cycle culminated in an industrial boom, thereby also driving house prices to a peak in 1995. At this peak, some realities of the Indian economy (poor bank penetration, high interest rates, non-transparent real estate market, etc.) came to fore, bringing a correction in market prices. As the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) erupted in the late 1990s, residential prices witnessed a significant drop, returning to the levels witnessed in the early 1990s.

It took approximately 3-4 years for Indian real estate to recover from the AFC shock. A handful of critical national employment-oriented policies and a reduced interest rate environment instituted by the NDA-led government laid the foundation for a revival in residential real estate prices during the early 2000s. Demand for quality residential apartments began to rise, and was increasingly addressed by developers, powered with money coming through the FDI route which had opened up since 2005.

In 2005, the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), which facilitated huge investments into building infrastructure to connect larger cities with 60+ smaller cities and towns, provided a fillip to overall real estate sentiment.

At the peak of prices during 2008, what emerged was a large accumulation of debt with almost every stakeholder – homebuyers (large mortgages accrued in the quest for buying more houses in a rising price scenario), developers (large accumulation of land parcels), and banks/lending institutions (exposure to outstanding loans to the real estate sector, which was now looking overheated). The ensuing economic slowdown and risk of job losses led to halt of the price rally. Thus, the two cycles of real estate that India has witnessed over the last 2 decades or so, has seen policy stimulus in the beginning and an overheated market in the end.

Reforms Targeted At The Real Estate Sector

Against the backdrop of a rising economy and concurrent income growth, the real estate sector has witnessed tremendous growth over the last 10-12 years. Government policies were at the crux, providing the necessary stimulus. However, while on one hand these real estate policies improved the housing situation in general, they also have elements that can be seen as detrimental to the real estate industry’s business viability. With the advent of the union budget season for 2014, it is time to review these policies and highlight the gaps.

- Repealing the Urban Land Ceiling (ULC) Act of 1976

The Urban Land Ceiling Act, 1976, was enacted with the intention of making land hoarding impossible for individuals or corporate entities which had the capacity to do so. The Act gave the state government the right to acquire and dispose excess land (as specified in the Act) from individuals and entities, thereby serving the common good. However, the Act became one of the main reasons for the short supply of land and therefore led to unaffordable land prices.

Under JNNURM, 29 states have now repealed this Act while two others still need to do so. The benefits of this reform are evident from the Gujarat and Nagpur examples. The Gujarat government transferred their surplus land to urban local bodies at nominal rates for projects focused on housing for EWS/LIG households. Likewise, Nagpur witnessed an increased supply of land for development as well as for investment after repealing the act.

Even while certain states have adopted the repeal Act, there are concerns regarding the lack of implementation by local authorities in certain districts. For instance, the Maharashtra Chamber of Housing Industry contends that the provisions of the ULC Repeal Act are still not in force, and are subject to discretionary interpretation and insistence of NOC from competent authorities. A complete repeal of this Act would unleash positive changes in terms of larger land supply and relatively affordable land prices. The budget can look forward to improve the implementation mechanism.

- Repealing the Rent Control Act

The Rent Control Legislation has been in existence for almost a century in India. The common intent of every state enacting the legislation was to protect tenants from forceful eviction and unfair rental hikes. However, the law failed to make provision for receipt against rent payments, rent increase against rising cost of building maintenance or inflation, repair work when the residential structure is at peril, etc. which renders the act inefficient. In an attempt to protect tenants, this Act has in fact created unfavorable terms for landlords, thereby making the entire model of rental housing unviable and inefficient.

To end the problems associated with this archaic law, a Model Rent Bill was circulated by the central government in 1992. It was an attempt to balance the interests of both the tenants and landlords. However, over the last two decades, only seven states have implemented the changes suggested in the Act. States such as Punjab and Goa have already experienced benefits from implementing the suggested changes.

A further push from the central government (possibly under the JNNURM scheme) would be needed to expedite the adoption of the model Rent Control Act. Its repeal could unleash a construction boom, as has been witnessed in many major cities all over the world (after they repealed their respective rent control acts). This is not only necessary to meet the growing unmet demand for housing but would also have a very favorable effect on employment generation.

- The New Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act

There have been innumerable cases of land owners being either exploited or dispossessed by force through diligently crafted contracts by corporate entities. The Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act tried to ensure maximum protection for land owners, who are often individuals and at times not fully aware of the future consequences of disowning their land. This Act has the potential to unlock all the land which has been locked for several years due to lack of ways and means that ensure fair compensation.

While the Act had the objective of balancing the interests of land owners and land acquirers, the final draft of the policy did not really deliver on this front. The clauses that appear in the Act not only ensure that land costs go up for the acquirer, but it also renders the acquisition process more complex and time-consuming. This is evident in the clauses pertaining to obtaining mandatory consent of 80% of the owners, future incremental gains from land transactions to be shared by the land owners, and different resettlement procedures for different sections of the population (such as scheduled castes/tribes).

- Service Tax Abatement On Construction Activity

In June 2012, the Ministry of Finance provided an exemption from service tax on construction activities related to single residential units or low-cost housing (carpet area of 60 sq. meters or less). The policy of levying service tax on construction services of under-construction apartments (which do not have completion certificates) added to escalation in cost to buyers. Due to non-availability of large capital sums and easy accessibility of EMI finance, the urban populace invests in real estate by taking loans. This includes the inbuilt costs of overdraft, which is further compounded by the imposition of service tax.

Exemption from service tax is provided for construction of residential complexes which are a part of the JNNURM and Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY). JNNURM and RAY are flagship schemes of the government of India to provide shelter for the poor and the disadvantaged.

- Consolidated FDI Policy

The Indian real estate industry has been on a roller-coaster ride since 2005. Consequent to the government’s policy to allow Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in this sector via Press Note 2, the sector has witnessed a boom in investment and developmental activities. The FDI channel was opened up under the automatic route in townships, housing, built-up infrastructure and construction development projects.

The main intention behind opening up the real estate sector to 100% FDI was to bridge the huge shortage of housing in the country, and to attract new technologies into the housing sector. The sector not only witnessed entry of many new domestic realty players but also the arrival of many foreign real estate investment companies – including private equity funds, pension funds and development companies – all lured by the high returns on investments.

However, lack of consistency in rules relating to the development of SEZs, increased monitoring of the sector by regulatory agencies, tightening of rules for lending to the real estate sector and increase of key rates by the RBI several times during the last one year have arrested the growth of the real estate sector.

There is a very clearly defined need to streamline government policies and introduce reforms. The key challenges that the Indian real estate industry is facing today are lack of clear land titles, absence of title insurance, absence of industry status, lack of adequate sources of finance, shortage of labor, rising manpower and material costs and a snail-like project approval process, among others